From: Burwash, Canada’s Western Arctic, pp 72-73

“During 1928-29 the writer again visited this area, spending the winter at Gjoa Haven. In April, 1929, both of the old men above referred to, Enukshakak and Nowya, visited Gjoa Haven and the writer secured the following statement from them. It may be said that both of the above natives, Enukshakak and Nowya, are men apparently of more than sixty years of age. This is, of course, a matter of conjecture as no primitive Eskimo has any precise knowledge of his age nor in fact does he think in numbers greater than ten. In estimated ages of the old Eskimos due allowance must be made as much depends upon the judgment of the person making the estimate. Both Enukshakak and Nowya were in agreement as to the details as hereafter recited.

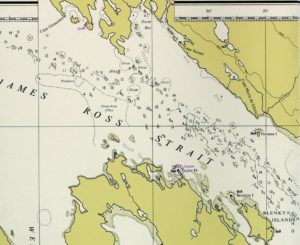

When they were both young men, possibly twenty years of age, they were hunting on the ice in the area immediately northeast of Matty island. When crossing a low flat island they came upon a cache of wooden cases carefully piled near the centre of the island and about three hundred feet from the water.

As described by them this cache covered an area twenty feet long and five feet broad and was taller than they were (more than five feet). The cache consisted of wooden cases which contained materials unknown to them, all of which were enclosed in tin containers, some of which were painted red. To them and one other native with whom they shared the find, the wood in the outer casings formed the only prize. They said that on the outside of the pile of boxes the wood appeared old but the parts sheltered from the weather were still quite new. All of the boxes were opened by the natives and the wooden cases divided between them as the lumber was much desired for the manufacture of arrows. Enukshakak’s share was eleven cases, Nowya’s nine and their friend two, making twenty-two cases in all. After the wood had been divided they opened the tin containers but found them to contain materials of which they then had no knowledge. In a number they found a white powder which they called “white man’s snow” which they and their families threw up into the air to watch it blow away. Since learning more about the white man’s supplies they have come to the conclusion that some of the cases contained flour, some ship’s biscuits and some preserved meat, probably pemmican, but they were still uncertain as to the contents of a part of the cache. All of the tin containers were cut open but none of the contents eaten as they did not think they were good. The empty tin containers were left scattered on the ground. They also secured at this time a number of planks which they described as being approximately ten inches wide and three inches thick and more than fifteen feet long. These they found washed up on the shore of the island upon which they had found the cache and on the shore of a larger island nearby.

Before the time of the finding of the cache on the island the natives had frequently found wood (which, from their description, consisted of barrel staves) and thin iron (apparently barrel hoops) at various points along the coast lines in this area. The wreck itself which had long been known to the natives lay beneath the water about three-quarters of a mile off the coast of the island upon which the cache was found. At the time they found the cache no cases had been opened and all were still closely piled together, indicating that whoever had put the cache in position had not revisited it. Enukshakak and Nowya both gave it as their opinion that the boxes had been put on the island by white men who had come on the ship which lay on the reef offshore. When asked what remained upon the site of the cache both natives said that a few years ago when they had last visited the island only the marks of rusty tins were to be seen.

The writer visited this island in April, 1929, but found a low flat terrain still covered with snow and was therefore unable to even check up the rust stains which should still be in evidence.”