Our big day of suffering

Wednesday June 21, 1995

After the trials of yesterday, we awoke late and were slow starting. I pointed out that it was mid-summer’s day, the longest day of the year, so we should be able to make good progress. Jim, never slow off the mark, questioned the logic of this in the land of the midnight sun.

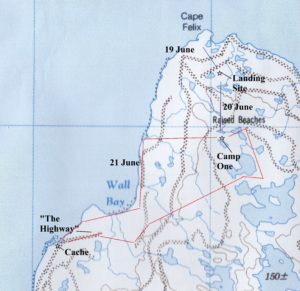

The main lesson of the day before was that we were overloaded. Rather than continuing to ferry our gear in short and soul-destroying hops, we decided to load up our packs and take some of the non-essential gear to a cache on the coast. This would also allow us to map out a feasible route. We could then return to camp and rest, ferrying the cart and remaining gear the next day.

Our planned course took us to the southwest to the northern point of Wall Bay. As the geography of the northwest coast consists of a series of eskers running parallel to the shore, this presented us with a seemingly-unending routine of scaling the eastern slopes, where the advancing summer had not yet melted all of the snow but had rendered it soft and heavy, to the bare rocky crests. Once there we scanned for the shortest route through the boggy trough between eskers, then carefully descended the dry rocky western slope and struggled through the next muddy section. It seemed to take forever to reach the coast. Every time we crested a ridge we expected to see the white glint of the pack ice in Victoria Strait, only to be repeatedly heartbroken to find another featureless ridge ahead.

After an exhausting five hours of seemingly Sisyphean labour we finally reached the coast. The plan, and prudent course, was to drop our gear here en cache, and return to camp with empty packs. This would have made for a fairly-short ten-hour day. Psychologically, we couldn’t face the labour of immediately retracing our path, and, buoyant with the relief of easier travelling on the gravel beach and the warmth of a gloriously bright afternoon, we decided to move the cache a few kilometers further to the southward. We were pleasantly surprised to find the walking fairly easy along the gravel beach, and we made good time. We briefly stopped when Rick thought that he saw a polar bear lurking in the offshore ice jumble. He slowly extracted our rifle from its cover, and we had a few anxious moments until it became apparent that either this was a totally-immobile bear or a bear-shaped piece of ice. It proved to be the latter, and we, somewhat shamefacedly, laughed at ourselves about the phantom bear and set off south with a light step, ignoring the reality that every step was taking us further from our base. Imprudently taking the easy path rather than retracing a difficult one would become the theme of the day.

I knew that the easy travel could not last. As we snacked on a cold lunch we huddled over the chart that showed two rivers emptying into Wall Bay to the south of us. But, carrying on, we soon found that at this season those channels actually formed a wide delta of wet sucking mud covered by a few inches of water. Most of these were easily waded, only one required a diversion inland to find shallower water. Jim and I had rubber boots, but Rick’s ankle boots were too low and he immediately flooded them. That would later have dire consequences.

Jim Garnett: “You had to pick your route through the various terrain. Some terrain was much better than the other, even if it meant going along in an S-shaped route rather than a bee-line … I felt fortunate that my boots worked so well. The rubber boots that I brought up … steel shank, steel-toed dairy farmer rubber boots, they were. I loved them. They fit my feet well. I don’t know if I had inserts. I probably — you know, the felt ones. Plus, my heavy socks and I tried not to get them wet at all. I had my hiking boots also and they worked well too, but I didn’t want to get them wet. There were times when the hiking boots were good but I more or less lived in those [rubber] boots. Dealing with the boots was a key issue of enjoying the trip as whole.”

By late afternoon the horrors of Wall Bay were left behind. About two kilometers to the south we reached a dry section on a small point where a large piece of driftwood served as a prominent feature. Agreeing that this provided a perfect landmark, we established our cache here, marking it with fluorescent tape in case of later ice fog.

Jim took a photo of me resting here, looking rather upset, as is characteristic of me when someone takes my picture. The darkness of my mood here had nothing to do with Jim, but was caused by my sudden tiredness, and the realization that we now faced a difficult return to camp. I was also desperately thirsty. Having planned only a quick trip to the shore and return, I had left camp with only two litres of gatorade, and left the hand-pump filter assembly behind. I had, through a great test of will, saved one litre for our return, but I desperately wanted to gulp that down to assuage my parched throat. A few quick gulps here felt heavenly, but I forced myself to stop with slightly more than half a litre left, knowing that it would be needed to get me home.

The prudent plan was to retrace our tracks. No-one was excited reliving the muddy horrors of Wall Bay delta and labouring over the endless corduroy eskers between the coast and our longed-for tents. Although it had cost us so much labour, we were surprised that our distance travelled was only about thirteen kilometers. The GPS told us that the straight-line distance back to our camp was 9 km. But one never travels in a straight line on King William, and none of us relished the seven hours of hard slogging that awaited us if we retraced our steps from that morning.

When faced with unpleasant reality the tired human brain searches frantically for an easier alternative. As we rested at the cache I could clearly hear the Siren’s song, enticing us to a more direct alternate route home. Temporarily putting aside the knowledge of the fate of the poor sailors who heeded such calls, we noted that just inland from our current position was an inviting flat-topped ridge which seemingly led directly toward our camp. In hopes that this would take us far enough inland to avoid the Wall Bay marsh we set off with now-empty packs and a light step along the ridge (quickly christened “the highway”) and found it excellent walking. Predictably, this leap into the geographical unknown proved disastrous – the “highway” ended abruptly, and the next ridge lay on the other side of an extensive swampy lowland that probably fed the delta at Wall Bay. It was the exact obstacle we had tried to avoid.

As we surveyed the inland terrain of alternating low limestone ridge and sodden muskeg, we briefly discussed returning to the coast. Reluctant to throw away the invested sweat equity, we decided to cross to the next visible ridge to see whether conditions dried out further inland. The next ridge appeared to be only two kilometers to the northeast, and we somewhat over-optimistically hoped that it would prove to be the largest expanse of muck that we would have to contend with.

Jim Garnett: [O]nce we had to turn off of that [the freeway] I took that change in terrain just as a matter of consequence because it was obviously there. You could see it. You can see everything up there so far anyway. You know it’s there, you’re not caught by surprise, but now you’re in it. … How did that workout overall for our route finding? … We were on a route and I just kept walking.

The crossing of that muskeg valley was an unending slog through sucking mud, calf-deep water (which was deeper than our boots – we were all now wet-footed) and mushy tundra. At seven pm, halfway across, we stopped to make our daily scheduled radio contact with George at base camp. Radio reception had so far been very poor but when I surprisingly made contact George wanted to chat, and he was probably dismayed at my curt conversation and abrupt signoff, unaware that as I stood in place I could feel myself quickly sinking deeper into the mud and stagnant water. Another minute of conversation and I would have required a crane to extract myself!

By eight o’clock we had finally gained the far ridge where we collapsed in exhaustion. My boots were heavily encased in over two centimeters of solid stinking yellow mud and I scraped this off with a piece of sharp rock. As I removed them to pour out the fetid water and wring the liners, I decided to change into my spare pair of dry socks as well. Rick, who had no spare socks and had been wearing wet boots since Wall Bay, looked wistfully at my own temporarily dry feet. It was an almost pointless exercise, as the felt linings of my boots retained the water, and a few steps into the next bog my boots had refilled with water. Meanwhile Jim, who was the most energetic of the three of us, moved to the highest point of the ridge to survey the route.

He returned with bad news. This second ridge was even shorter than our “highway” and petered out in only a few hundred meters. Not surprisingly, there was another swamp between our position and the next ridge, and it seemed to be about the same size as what we had just come through! As if to emphasize our darkening mood, the sun had again been swallowed by encroaching ice-mist blown off Victoria Strait by a resurgent strong, and very cold, northwest wind.

The GPS told us that we were still 6 kilometers from camp. The next hours passed in an unending sequence of swampy muskeg, followed by the brief relief of a dry ridge, followed by muck again. Visibility was now no more than a hundred meters, and as the temperature continued to fall each of us was submerged in his silent shuffling sphere of misery.

Jim Garnett: We just had to keep on going and hopefully the next little patch of stuff will be better. You’re up to your knees, you’re over the top of your boots in a lot of these little ponds that you’re trudging through and it’s just one after another, making your way through, hour after hour after hour. [chuckles] Stopping every now and then I guess but we just had to keep on going. I don’t remember any real drive to keep going, but I knew we had to. Sometimes the hot spots on top of the bog worked really well, other times they were up to your knees.

At first, we stayed close together, but as the trek wore on I slowly fell behind. A piercing abdominal pain periodically struck me, accompanied by a burning urgency to urinate. As I had finished my water supply hours before I wondered if this was a symptom of Arctic dehydration. I would usually find that by the time that I had frantically clawed my way through multiple layers of clothing the feeling had passed. When I did urinate only a few low-pressure drops resulted, disgustingly dribbling down the outside of my wind-pants and immediately forming little deltas of frozen piss. Charming! I would later learn from a doctor friend that what I was experiencing was probably advanced Cold diuresis, a warning sign of impending hypothermia.

Both of my companions were solicitous and stood waiting for me while these episodes passed. Eventually, lost in their private worlds, they stopped looking back and often passed out of sight over the next ridge or into the mist. This always caused me a minor panic as I contemplated becoming separated from them (even though I had the only GPS and was navigating back to the tents). Each time I would rush to catch sight of them again and would temporarily build up a sweat, which then froze into a surface skin of ice when I resumed my normal zombie pace.

Although we were all exhausted, we couldn’t stop in the muck or we would immediately begin to sink in. Even when we reached the dry stability of a ridge we found that any rest could not last for more than a very few minutes. Very rarely there was an erratic boulder large enough to lean or sit on, but we derived small comfort from our rock perch for they had been frozen for thousands of years and soon began to suck our body heat through the seat of our pants, causing a deep chill to invade our bodies.

The deteriorating weather and constant exertion had sapped us psychologically as well. Only a few hours before we had been laughing and joking in the warming sunshine of the coast. Now a strange lassitude and sleepiness had settled over me and I had to continually fight the urge to lie down on the flat broken limestone for a short nap during these stops. I knew the effort to stand up again would be too much. I also knew that this was a dangerous idea.

I was beginning to feel a kinship with the retreating Franklin crews on a level I had not anticipated. It was impossible not to think of the poor marchers from the Erebus and Terror, weakened by years of confinement in their ships, who had faced the same challenges of foot travel on King William Island. Less than a hundred miles to the south of us, 143 years ago, McClintock had found the sad remains of one of Franklin’s men who had apparently, like us, “selected the bare ridge top, as affording the least tiresome walking.”

Weakened by his ordeal, this poor man had “fallen upon his face in the position in which we found him. It is probable that, hungry and exhausted, he suffered himself to fall asleep when in this position, and that his last moments were undisturbed by suffering … [this] brought most forcibly to my recollection the extreme danger of being overcome by sleep under intense cold. It was a melancholy truth that the old [Inuit] woman spoke when she said, “they fell down and died as they walked along.””

Our experience was not unique. Unsurprisingly, almost every first-hand account of extensive walking travel on King William Island features the same description of the physical difficulties posed by sodden tundra, sharp rocks and confusing vistas. Less remarked upon are the mental challenges posed by this terrain. Steve Trafton, on a trek through Douglas Bay in 1977, had also found his energy reserves fading. Turning his back to the wind he sat to rest for a few minutes “and then I sort of zoned out – lost track of time … intense cold allowed lethargy to settle in. We started to get sleepy. Though we should have been alarmed, we just didn’t care. None of us wanted to do anything more than sit and rest.”

Only a few days after our own expedition, Ernie Coleman, during his exploration south of Collinson Inlet, noted the same thing. His mind “started to talk to me. The words were clear and their meaning unmistakable. I was told that if I did not survive – so what? In a hundred years, who would care less? A lot of people had died on this coast; it would be very easy to join them. All I had to do was to lie down and go to sleep.”

We all realised the insidious danger of advancing hypothermia, and, failing anywhere to sit, kept our rests very short. We just silently stood and waited a few minutes for the sweat to freeze on our faces before nodding at each other and shuffling on. I was never the first to start again.

I had been on long and difficult marches before, and now began to implement techniques that had proven useful in the past. One was to distract my brain by softly singing show tunes to myself. I performed a one-man show of My Fair Lady and Jesus Christ Superstar, being, I am sure, local premiers of each performance. The tundra ptarmigan were singularly unimpressed.

I also fell back on an old boot-camp trick of “effort and reward.” I would pick out a rock ahead and promise to reward myself with a 30-count rest when I reached it. Unfortunately this flat land offered no vertical referents to aid in perspective, no trees or bushes to help in gauging distance. The black, seemingly knee-high erratic boulder ahead turned out to be a small close feature, or never seemed to get closer, and turned out to be a more distant meter-and-a-half-high. During each rest, my mind tended to wander, and I lost track of the count, eventually moving on only when my companions were about to disappear into the mist or over the top of the next ridge.

As the hours passed, we stumbled along in a straggling line. Jim was now in front marching resolutely on without looking back, followed by Rick (who still waited for me occasionally), with myself bringing up a slow rear. I had settled into a state of automated suffering, mentally unable to process much more than the requirements for my next footfall, with an endless loop of Frost’s line “miles to go before I sleep” as mental background.

In spite of his ruined feet, Rick was emerging as the hero of the day. Whenever I stopped to take a GPS fix, he hurried ahead to stop Jim. Unwilling to surrender ground obtained by suffering, Jim did not come back to me, but simply stood still where he was and awaited events. Rick would then retrace his steps to me. It would take a few minutes for the orbiting satellites to be acquired, but eventually we would determine our position and implement any necessary course correction. Rick would then move up to Jim’s position, indicate our new path to him, and we would all move on, Rick having covered the distance between Jim and myself three times.

Each time I pulled the GPS out of my inner fleece pocket it seemed to be harder and harder to make sense of the numbers. It reminded me of a time when, during a particularly long practice attack in my submarine, the combination of heat and a very low oxygen level had rendered every routine plot calculation almost impossibly difficult. The effect had been insidious and largely unnoticed until one realized that even simple and routine tasks were unaccountably perplexing.

I could tell that my mental state had been steadily degrading for hours. It was obvious to my companions that during our navigational stops I was having difficulty plotting our latitude and longitude on our small topographic map and puzzling over whether we should now head northwest or northeast. I had been a professional navigator for my entire career, but faced with useless magnetic compasses, inexact contour maps, and outdated photo imagery of a constantly-changing drainage pattern, GPS was the best tool available.

Now GPS is woven into the modern world, an expected and unremarked element in our cars and cellular phones, but in 1995 our Magellan receiver was a first-generation handheld unit, and the signal was still intentionally degraded by the US Military to provide no better than 1000m accuracy. Unfortunately, in our current circumstances, that was about five times our current visibility in the ice fog.

As we approached our camp’s position course corrections became larger and more important. The frequent fixes also gave me a built-in excuse for a rest without impugning my masculinity. I found that I craved the reassurance of the GPS, it told me that I would not lead my friends too far in the wrong direction as a result of any single navigational mistake on my part. This source of comfort was slowly turning into a panic as the receiver began to fail. The screen was becoming increasingly dark as we stumbled north, and I soon realized that the cold night was freezing the batteries and that too-frequent fixes would drain them before we found our camp. To preserve battery life, I reduced the frequency of fixes and moved the receiver five clothing layers down, right next to my skin.

Eventually, we crested what should have been the last ridge, fully expecting to find our tents nestled beside their lake. Instead, crushingly, we found a large muskeg field blocking our path ahead. A check of the GPS showed that we were now two kilometers southeast of our camp, having somehow missed the north-running ridge that had been our target. The map showed that our camp was at the northwest corner of what should be the next large lake to our north, so we trudged in that direction. We confidently expected to follow the lake along its western shore (on our right) but when we eventually arrived the lake was to our left, we were inexplicably on its eastern shore. According to the map, this was an impossibility!

We could do no more than assume that we had stumbled onto an uncharted pond, or that the drainage patterns had changed since our map was printed. As we continued north, we continued to look to the east for our tents or the charted lake but, according to the GPS we had now somehow passed our camp which was 400 meters to the southwest! In our confusion and disappointment, Rick and Jim were becoming understandably skeptical of my expertise.

Jim Garnett: I think we were checking the GPS and the map, trying to pinpoint our location. … There’s not a thing you can do other than change route the next time and hopefully amend. That’ll be it. I probably had my doubts about the GPS coordinates and all that but there was nothing we could do.

Even allowing for the limits of the GPS, and our perhaps-outdated topographical chart, nothing on the ground was matching our expectations. My receiver insisted that we were close to the tents. Our only solution seemed to be to stay where we were and await the eventual lifting of the ice-fog to get our bearings. Failing to find our camp, I decided we should commence a sector-search pattern. This would at least serve to keep us warm. From their blank expressions I could see that my companions, unfamiliar with the arcana of maritime search techniques, were not comfortable with the concepts of datums and crosslegs. I decided to simplify, and soon we were walking abreast in an expanding circle pattern, with each man maintaining visibility with his next neighbour.

After about twenty minutes Rick saw a strange patch of bright red through the grey mist. Although we could not remember anything in camp that was red (our tents were, unhelpfully, grey and brown – the predominant background colours) we knew that this was unnatural and moved closer to investigate. After a few more steps we saw that Rick and Jim’s Moss tent had been overturned and was now showing us its red nylon floor! Salvation!

In our absence the wind had wreaked havoc on our camp. The overturned tent was only saved from sailing into the lake by a solitary straining tie-down, while my tent was semi-flattened with the two windward guys threatening to break free from their heavy rock anchors at any minute. As we stood surveying the wreckage Jim started to chuckle – the first sound from our jokester in hours. “Good thing Margaret can’t see what we’ve done to her tent,” he said, and pretty soon we were all laughing insanely.

The surge of adrenaline from finding camp was short-lived and after re-erecting the tents I started to appreciate just how beaten up we all were. Rick’s feet had been alternately soaked and frozen all day, and as Jim solicitously helped him remove his boots and socks we could see the result – they were grey and lifeless blocks. Jim slowly rubbed the circulation back into them, but they remained worryingly swollen and pasty.

Jim Garnett: “I actually felt I had to take on a role when we finally got back after our big day of suffering, because I realized that at the time I was in actually pretty good shape. I recognized the situation and I felt like I had to kind of assume the role of morale support, and not be a brash leader or anything but be the guy who talks to the car accident victim and holds his hand and says, “Hey don’t worry, help is on the way” and everything. That kind of support person in the team of us then. I felt I had to take on that role at that point in time when we finally made it back and we’re going to make it and to recuperate.

Once our tents had been restored to order, I left my companions to address my own greatest need. My reserve camp Nalgene water bottle was almost entirely frozen solid, but a little liquid was visible in the cracks running through the cylinder of ice. I managed to extract a few mouthfuls of nectar and immediately felt somewhat restored. Extracting my knife, I started chipping the solid ice around the opening into flakes, and each one immediately took the title of “best fluid to ever enter my mouth,” but after a dozen or so I could feel the interior chilling effect on my half-frozen body, and forced myself to stop rather than induce (accentuate?) hypothermia.

Next, I stared at my boots, they had been reduced to solid shapeless extensions of my legs, encrusted in frozen slime. Walking in knee-deep water and muck had made this frozen carapace into one indistinguishable mass, and I had to guess where my boot-tops ended and my leg began. I turned my knife on this mess and semi-carefully started to hack away. I worried about the effect on my tent floor once the disgusting flakes melted (needlessly as it turned out since the tent never reached melting temperature, in the morning I simply brushed them out.)

Eventually, I reached the point where the boots were loosened enough to extract my feet, although the knife-scars on the leather tops would later reveal how closely I had come to slicing into my legs. That allowed me to strip off my similarly-disgusting wind pants. The effort had been enough to temporarily warm me, but soon the cold crept back and a wave of exhaustion led to an uncaring disregard for the normal routines of removing my remaining outer layers and preparing for bed. I simply drew my unzipped sleeping bag over myself as a cover and wallowed in self-pity.

I shivered for what seemed like hours until my core body heat was restored. The sounds of low murmuring emanated from Jim and Rick’s tent, where they were still dealing with their issues. It had been one of the physically hardest days of my life but, as it always does, physical distress eventually faded and I drifted off in blessed sleep.

Distance made good – 9 km, distance travelled – 22 km.