St. Roch II Voyage of Rediscovery (2000)

When Jim Delgado visited Prince Rupert in the early spring of 2000, Franca and I took him to dinner. I had heard about the St. Roch II expedition and even briefly considered volunteering as crew, but my job and family prevented that. However, when Jim mentioned that there would be an enforced two-week delay between Cambridge Bay and James Ross Strait while they waited for breakup, I could see my chance for more wreck surveying. He volunteered a spot for me if I could self-fund, and I was overjoyed.

Jim, George Hobson and I flew up to Cambay together, but the ships were delayed, so we had a day to wait. On Saturday, August 12th, Jim and George went off in the Adlair Beaver to look for the “Matty Is.” wreck, and I had a glorious day to myself with nothing much to do. I packed a snack and backpacked around the bay to the cemetery and Old Town, reading all the plaques and listening to my new Cheryl Crow CD. The day was warm, so I laid out some plywood and decided to read/snooze the afternoon away from the wind behind a rock. After a while, I looked up and saw the masts of a large ship over the hill – the Simon Fraser had arrived. I walked back into town in a great mood and met some of the crew coming up the hill (Paul, Rena and Diane) – they were looking for a phone. I directed them to the store and carried on. That night, after the St. Roch II/Nadon had also entered port and J&G had returned from their fruitless flight, I joined them in Ken Burton’s hotel room for drinks and a planning session. I agreed to bring my gear to the Nadon at the dock in the morning at 9 and be transferred to the anchored Simon Fraser. We wouldn’t leave port for another few days, but it would save on my hotel bills.

The next day (August 13th, 2000), I arrived on the dock at 8:30, but everyone on the Nadon was still sleeping or at breakfast. The stores truck was already there so I helped the driver unload and put the food on the quarterdeck. The crew eventually came out and initially thought I was a delivery man (Ken was the only one who knew me, and he was still at the hotel). I finished storing and then moved my personal baggage aboard. The stores were destined for the Simon Fraser, and we left the bulwark and sailed out to her in the middle of the bay. As we got closer, we swung for a port-side approach, and I noticed that the crew were lined up at the waist, awaiting us. The two I noticed most were the guy with the long grey beard whom I had met yesterday (turned out to be Paul – the bos’n) and, to his right, a very pretty young girl smiling at us as if we were her long-lost friends.

As we started to transfer the stores, I was at the end of the chain and passed things on to either Paul or the pretty girl. She didn’t look that big, and I was impressed by her strength. She never stopped smiling. When the stores were half-transferred, the line on the Nadon was starting to stretch out, so I recommended that someone from Simon Fraser might want to come over to restore our spacing. The girl immediately jumped over the gunwale and took position to my right. This would mean that she would have to lift the stores up a few feet to the larger ship, so I suggested we switch places so that she could pass to me, as I would have a shorter lift. She smiled and said, “ok,” we worked like that until the stores were finished. And that was how I met Amie Gibbins.

There were social duties in Cambay in the next two days – a reception at the visitor’s centre and a BBQ out of town. At the first I met local author David Pelly and told him that his book Qikaaluktut: Images of Inuit Life had long held a place of honour on my bookshelf at home. He had also read Unravelling, and our impromptu mutual admiration meeting gave him an idea. Beckoning me to follow him, we went to the attached bookstore, and he pulled my book from the shelf with the request that I autograph it. Full in the flush of an author whose work is appreciated, I opened the book to the title page, only to wryly close it again and pass it back to him. “You don’t sell many of these,” I remarked and told him that I had actually signed the book in 1997 when passing through town.

The BBQ, hosted by the Glawson family, was a great break from work, with most of the community and crew in attendance. I remember little of it except the extravagant level of hospitality and the fact that, probably a little unsteady from my enjoyment of it, I split my jeans getting into the zodiac to return to my bunk on the Simon Fraser.

On the passage to Kirkwall, the main topic of conversation among the crew was the recent sinking of a Russian submarine (the Kursk, which sank on August 12th). This was dominating the news. As an ex-submariner, everyone seemed to think I should have some insights into this, but the details on the radio were too sketchy. All I could say was that I hoped the crew were okay, but privately, I had doubts.

I spent most of the passage to the search area aboard the St. Roch II, inputting waypoints for the search lines into their chart navigation system. We anchored for the night in a small southern bay of Jenny Lind Island, then rejoined the Simon Fraser, which had arrived at anchor near Kirkwall, after a quick morning run.

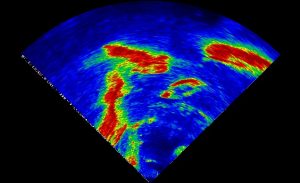

The next day, our survey began, and I was suddenly very busy with the work – spending 16+ hours a day out on the Nadon/St. Roch II with Bob Asplin and Mark Treverrow. These two gentlemen, equal parts technical experts and stand-up comedians, made the long days of uneventful survey bearable. Despite the inevitable problems of mechanical failure, weather, and navigation in uncharted waters, we covered a significant portion of the search box I had identified. Despite a few hopeful hits, all of which turned out on investigation to be geological features, the bottom was generally flat and featureless. No signs of a wreck or debris field were seen, and none of the shore searches conducted by George and his teams of volunteers found any cultural artifacts that could confidently ascribed to the Franklin expedition.

and Mark Treverrow thrilled to stare at the sonar all day.

One morning, near the end of our survey, I was having breakfast in the mess. By now, it was apparent that we wouldn’t have time to complete the planned work. A guy in overalls (Bill Robinson) sat opposite me and asked me what was next. I recognized him as part of the engine room staff (he was working as an oiler), but I had not interacted much with him in the normal course of our duties. I mentioned that before the present opportunity arose, I had been planning to do a small sled-based expedition with a magnetometer. I was not yet ready to abandon the search, but on arrival home I would put together a “prospectus” for that expedition and shop it around for sponsors. Bill immediately said that he could probably raise money. I knew nothing about him, so I didn’t think he was a likely prospect.

Amie was at another table and apparently eavesdropping on our conversation. She asked how much money I would need, and when I said $30-50,000, she said that she worked in a film-production crew and that was “less than the cost of a good lens.” She said she, too, might be able to find a sponsor. Again, amazed at the serendipity of fate, I promised to send the “prospectus” of the planned expedition to both of them on my return.