The Matty Island Shoals

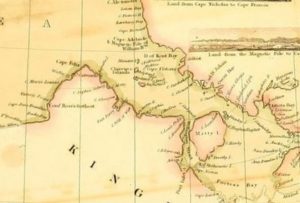

In late August or early September 1846, Sir John Franklin and his two captains faced a problem. Having brought their ships south through the previously unknown Peel Sound, they were approaching known, if imperfectly charted, territory. As they approached King William’s Island (then known as King William’s Land), they would enter into known geography at Cape Felix, visited and named by James Clark Ross sixteen years earlier. They had a decision to make to proceed to the west or the east of that cape.

It is common to read that one stupid decision by its leader caused Sir John Franklin’s 1845 expedition’s tragedy—the choice of ice-clogged Victoria Strait rather than James Ross Strait, which, unknown to them, is usually free of ice, as its choice of route. Yet, as with most things about this expedition, the story may not be so straightforward.

Franklin could only operate on the information that he had at the time. The most significant source would be the charts and narrative of the Ross expedition of 1829-34. During that journey, James Clark Ross had traversed the territory ahead of Franklin. Ross had noted that to the west of Cape Felix lay Victoria Strait. He had seen no trace of land to the west and noted the favourable trend of the coast toward Point Turnagain on the mainland coast. That point, reached by Franklin himself on an earlier expedition, was the portal to a known passage to the Pacific. That would undoubtedly tempt Franklin as the most direct way toward his goal. Ross did warn, however, that the route would not be easy, for “the pack of ice which had, in the autumn of the last year, been pressed against that shore, consisted of the heaviest masses that I had ever seen in such a situation … the lighter floes had been thrown up, on some parts of the coast, in a most extraordinary and incredible manner; turning up large quantities of the shingle before them, and, in some places, having travelled as much as half a mile beyond the limits of the highest tide mark.” This ice resulted from the strong stream of ice that flows south through the still-undiscovered McClintock Channel and piles up on the coast of King William Island. The ice dynamics are now well understood, but Franklin could not know this at the time.

To the east of Cape Felix, Ross offered another option. Here, Ross had mentioned finding two natural harbours, one of which (Port Parry) was an “excellent harbour, could such a harbour ever be of any use: and its entrance, which is two miles wide, is divided in the middle by an islet that would effectually cover it from the invasion of heavy ice.”

As winter quickly approached, Franklin, aware that there were no known refuges to the west between Cape Felix and Cape Turnagain (Cambridge Bay was not yet discovered by Europeans), would have seriously considered that Ross’ harbour could “be of any use.”

In his undoubtedly careful study of Ross’ narrative, Franklin would also be intrigued by another possibility offered by that direction. Ross’ guide Ooblooria had spoken of a narrow strip of water in that direction: a “continuous open sea, or a sea free of all ice during the summer.”

When travelling through this area, Ross noted that everything was so flat and uniformly covered with snow that he had difficulty telling whether he was traversing over land or water. Retracing his route, James would wrongly conclude that King William’s Land was a westward-extending peninsula connected to Boothia, and his charts would show “Poctes Bay” with a dotted line to reflect his uncertainty. In the expedition Narrative, buried in the Appendix, it was surmised that King William’s Land might actually be an island and that “Poctes Bay” was, in fact, an open channel which eventually connected to Simpson Strait.

We now know that “Poctes Bay” is, in fact, the northern entrance of James Ross Strait and that Ooblooria was more accurate than James Ross in his geography. This is the preferred route through the “southern” North-West Passage (the only one passable by small wooden ships) and was later used successfully by Amundsen, Larsen, and others.

And yet we know that Franklin did take his ships to the west, as the Victory Point record confirms that they were beset in Victoria Strait on Sept. 12, 1846. It is not stated whether that was his first choice or whether he had attempted the eastern solution first and been forced to abandon it.

I have explored this possibility elsewhere to explain the persistent rumours of a wreck near Matty Island and tales of a cache ashore. However, what is rarely appreciated by the casual reader is the navigational difficulties that this eastern passage would pose for Franklin’s large and unwieldy ships.

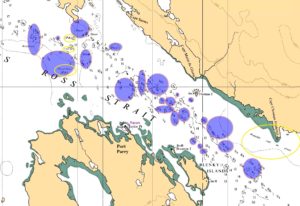

This might not be as apparent to the non-navigator. The simple small-scale maps that usually accompany this discussion have no indication of water depth or currents. Still, to anyone who has the ability to read a nautical chart, the difficulties of the eastern route become glaringly obvious. Even in modern times, with the aid of modern navigation charts, GPS and navigation beacons ashore to assist, the passage through this area is difficult. It would give any ship’s master moments of concern.

Amundsen, the first to attempt the passage without these aids in 1903, almost came to grief:

“It seemed we had got on a projecting shoal. The vessel struck very hard several times, and some splinters of the false keel floated up … these islands were so surrounded by banks that it was hopeless to get to leeward of them without grounding … but we no sooner got ten fathoms than it began to get shallow again towards Matty Island … we ran aground … we had got in among the shallows jutting out from the islands. … Shortly after, we struck again, got off, and grounded again, this time for good. … The bank we had grounded on was a large submerged reef, branching out in all directions. It extended to the west towards Boothia, as far as I could see. The land right to leeward was probably Matty Island.”

Amundsen eventually freed his ship by tossing heavy cargo overboard and completed the Northwest Passage. Yet he noted that the Matty Island shoal complex posed the most serious difficulty in the entire enterprise. It must be remembered that Amundsen’s Gjøa was a relatively small yacht of 46 tons compared to Franklin’s ships, which were six times as heavy. Gjøa drew 1.8m (six feet) – 3m (10 feet) of water when loaded, while the Erebus at Terror drew 4.3m (14 feet) – 5m (17 feet) when they were overloaded at the Whalefish Islands. The consumption of stores may have reduced this during the first year of the Franklin expedition. Even so, his ships would still necessarily be deeper than their designed draft (when empty of stores), so the following assumes a minimum of 6 meters of water as required for passage.

The passage of the RCMP vessel St. Roch in 1941, on the first west-to-east transit of the Northwest Passage, also encountered difficulties in the area. Here, Captain Larsen, in his own words, “nearly lost the ship, as the waters were full of shoals.”

“Monday, September 1. 10:05, saw large shallow patch of Dundas Island, shortly after ran into shallow water between Matty Island and Spence Bay. Vessel turned about and proceeding back and forth slowly in search of deeper water, 2 ½ fathoms shallowest spot sounds … [Sept 3] encountered several shoals, but water generally good if soundings taken frequently. Land covered with snow and hard to distinguish from ice at times.”

Thirty-six years later, Willy de Roos took his small yacht Williwaw through Ross Strait and noted the same reef “lying along the northern coast of Matty Island … Before long the depth is down to three fathoms (5.5m). ”

Large sections of the Canadian Arctic are still not hydrographically surveyed to modern standards. While the modern chart shows the preferred channel in some detail, even now, the chart shows large areas where there are no soundings or features with the “ED” (“existence doubtful”) or PD (“position doubtful”) designations. Creating a route through the maze of shoals that avoids hazards where the water depth is less than six meters remains quite daunting.

The Scott Polar Research Institute has tracked all transits of the Northwest Passage from Amundsen to the end of the 2024 navigation season. It notes seven different “passages” using various routes through the Arctic Archipelago.

Of these, Franklin’s route direct through Victoria Strait would have been #3, described as “the principal route; used by larger vessels of draft less than 14 m.” Route #4, the Ross and Rae Straits east of King William Island, is described as “a variant of route 3 for smaller vessels … only 6.4 m deep, it has shoals with complex currents.”

Of the 431 transits detailed, route #4 (Victoria Strait) was used, in both directions, 105 times (25%) by larger ice-capable vessels, and the eastern route #3 was mainly used by small sailboats and other vessels requiring ice-free passage, 66 times (15%).

Captain Bill Noon of the Canadian Coast Guard routinely took the Laurier, drawing 5.5m (18 ft) through this passage. Even with the aid of modern charts and beacons, which allow accurate fixing, he considered it “a pain to navigate.” He noted “a fair bit of current” and noted that “the ice will stack up” at the northern approaches to Ross Strait. In his opinion it “would have never looked attractive if they ventured … that way to look at options … I can not even imagine trying to get a sailing ship through this passage.”

He considered James Ross to be “very difficult and nerve-racking to navigate before the new charts came out … the land is low-lying and useless for fixing. We always followed the same track that was carefully maintained year to year on the old charts we carried. The East Coast CG ships pretty much avoided this area as it required local knowledge to do comfortably.”

Although there are only faint clues that Franklin might have initially tried the eastern variant route, either to search for Ross’ excellent harbour as a winter refuge, or Ooblooria’s “open sea” as an alternative passage, it would have been very difficult for him to successfully take his deep unwieldy ships that way.

Hello! This is my first comment here so I just wanted to give a

quick shout out and tell you I really enjoy reading through your posts.

Can you suggest any other blogs/websites/forums that cover the same topics?

Many thanks! https://menbehealth.wordpress.com/

Thanks. You might want to check out one of the excellent sites listed in the media>weblinks tab.