Anchors and Propellers

@ David C. Woodman 2025

It’s been over a decade since the wreck of HMS Erebus was found, largely intact, under the waters of the Canadian Arctic Ocean, followed by the discovery of her sister-ship HMS Terror in 2016. During this time, the marine archaeologists of Parks Canada have been diligently and meticulously investigating the wrecks during the short season allowed by the Arctic environment.

As an ex-diver, I appreciate Parks Canada’s work and wait expectantly each year to learn of the treasures discovered that season. I also recognize the high professional standards of the marine archeology team, which gives me confidence in the accuracy of any speculation about the possible implications of their discoveries. Their careful preservation and analysis of the yearly assortment of artifacts is a testament to their professional dedication. While each item is subject to considerable professional energy and research, these efforts are presented without extensive historical analysis, and in truth, there is little to be learned about the conduct or eventual fate of the Franklin expedition from the recovery of a beaker, eyeglass piece, hairbrush or artificial horizon. (Https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/nu/epaveswrecks)

Mainstream reconstructions of the conduct of the Franklin retreat still assume that the recorded desertion of the ships in April 1848 led to a single line of retreat that came to a tragic conclusion at or near Starvation Cove later that year. This has the advantage of simplicity, and so far, no physical evidence has emerged to invalidate it. However, the recorded histories of contemporary Inuit and their interactions with Franklin’s ships, while manned and wrecked, and the locations of the wrecks in unlikely places, cast this reconstruction in doubt.

More adventurous speculation considers that some crew returned to their ships after the 1848 desertion. This “return theory” has been posed almost from the first days of the investigation; McClintock (1859) remarked, “[t]hat some party did return, I felt convinced when I found that the sledge on which the boat rested was pointing to the north-east, exactly for the next point of land, as would be the case if returning to Point Victory and the ships; and also from the natives having told me that a dead man had been found on board.”

This latter observation, that a body had been found when the abandoned ship was first discovered, is well attested in the Inuit histories. Various ingenious theories have been advanced to address this tradition. For instance, Admiral Wright invoked a figurehead (neither of Franklin’s ships had one), which seemed unlikely since the stories told of the body “smelling bad” and that it was moved by the Inuit from a bunk to the deck “in the back part of the ship.”

When learning of the discovery of this wreck, identified as HMS Erebus, I anxiously awaited news of whether human remains had been found, as this would afford tangible support for this remembrance. As all 105 surviving crew deserted the ships in April 1848, discovering a body aboard would offer strong evidence of the supposed return to the ships. In the event, this assertion has been difficult to confirm or deny, as the after part of the wreck has collapsed. Human remains may lie underneath the damaged stern structure, and so far, this has been an unproductive clue.

The next potential indication of remanned ships would be crew-deployed anchors. Yet neither ship seems to have used their primary anchors in their current positions. In his excellent description of HMS Terror, Matthew Betts noted: ”[t]he 1839 profile plan describes the extensive number of anchors supplied to the vessels, all conveniently carried on the ice channels that surrounded each ship.” The official report of the Underwater Archaeology Team on Erebus for 2015/2016 confirmed that “the bower anchors appear to have been catted before the ship sank, given their position on the seabed under the eyes of the ship” and “the ship’s six (at least) supplementary anchors were still stowed on the ice channels before sinking.”

To date, the best evidence that the ships might have been remanned came from two of the most intriguing and underreported artifacts. The Erebus’ ice anchor, a crucial tool for securing the ship in icy conditions, and Terror’s propeller, a key component of the ship’s propulsion system, could potentially provide significant insights into the final days of the Franklin expedition.

The Erebus Ice Anchor

@ Parks Canada – Photo credit: Brett Seymour, Parks Canada, 2023

The narrative of the discovery and position of HMS Erebus among the islets of Wilmot and Crampton Bay is well known. How she arrived there, abandoned and taken by the wind and current encased in a floe of first-year ice, or, less likely, taken by the surviving crew, is uncertain. The ice anchor, discovered in 2023, might offer a clue.

Arctic exploratory vessels operating in uncharted water that contained random shoals often used ice anchors. The Inuit consistently stated that the Erebus, seen before sinking, was encased in first-year (formed in place, generally about two meters thick) ice near Grant Point. In this situation, an ice anchor would not necessarily be required. However, there are examples from other expeditions of cables that led to anchors in smooth ice or anchors being taken onto the ice for other reasons.

Therefore, the photo of the ice anchor in the debris field of the Erebus is interesting. This solitary ice anchor was found on the seabed, as confirmed to me by Jonathan Moore, in 2023 by underwater technician Aaron Griffin while doing the mooring inspections for the permanent anchors installed for the survey barge Qiniqtiryuaq. It was found 27m off the starboard (northern) side, sitting proudly on the seabed (pers comm.). This is notable as other heavy items, such as the two cannons, were found immediately adjacent to the hull. The anchor was not an element of the debris field surrounding the wreck, most of which lies immediately adjacent to the hull and reinforces the Inuit tradition of a gentle sinking, with the ship essentially upright and her masts sticking out of the water. It is not inconceivable that an anchor stowed on deck could have been displaced by ice action alone during the process. An indication of the extent of the debris field is that a portion of the ship’s wheel, admittedly much lighter than an anchor, was found 27m south of the main wreck.

In conversation with Moore about the ice anchor, he remained professionally noncommittal but intrigued. In his opinion, “whether the ice anchors were deployed cannot be determined.” It was “not possible to draw any firm conclusion on the question of deployment (i.e. a positive crew action implying a person(s) on board at some unknown time), which is, of course, a compelling question and one that immediately struck us.”

Further investigation of the debris field may clarify whether other ice anchors are present. If found, other ice anchors could provide evidence for human action rather than normal deposition during the sinking. Still, only one ice anchor has been found to date. Moore correctly remarked, “one would want to have a better idea of the presence/absence of ice anchors over the entire site and their overall spatial distribution … before drawing any conclusions.”

Although the location of the ice anchor is suggestive, it does not necessarily mean the ship was crewed right up to its final day. As the wreck lies so far from its 1848 desertion site, it seems unlikely that the ice anchor, deployed by the crew pre-desertion, could have remained close to the ship during a long and difficult passage through the turbulent pack ice. But they could have been deployed from Erebus before it was deserted near Grant Point, to a deeper old-ice protective floe or pressure ridge. This attached floe could then have served as a “bumper” as the ship pinballed, unmanned, south through the maze of islets choking Wilmot and Crampton Bay on its final journey to the eventual wreck site.

Terror’s Propeller

The other underreported archaeological find comes from the wreck of HMS Terror. In 2019, a Smithsonian magazine article by Megan Gannon reported an interview with Ryan Harris of the Parks Canada dive team that confirmed that Terror’s propeller had been found in place. This was an update on the published report of the 2017 survey, based on the side-scan sonar and multibeam data, which stated “the propeller trunk seems filled with wooden chocks.” That report admittedly noted that visibility was impaired. Although dark ROV images indicated that something was filling the aperture, it was concluded that “this feature needs to be examined further.” In 2019, with more diving time and better visibility, the archaeologists could determine that it was the propeller filling the aperture. In the 2019 article, Ryan Harris speculated about the implications of this discovery. He concluded that “the crew likely would have taken the propeller up” before deserting the ship.”

This fact and its implications have gone mainly unremarked upon in subsequent analysis, although mentioned in passing in Michael Smith’s 2021 biography of Crozier and Matthew Betts’s book HMS Terror. Betts boldly concluded that “at some unknown time after her desertion, a portion of the crew returned to and re-manned Terror. The primary evidence for this is the presence of the screw propeller deployed in its engaged position, something which would not have been intentionally done in the open pack ice owing to the vulnerability of the stern.”

Again, the Parks team was aware of the possibilities of this discovery but cautious in making definitive statements. Jonathan Moore confirmed to me recently that they had “given the fact of the propeller disposition a lot of thought.” Still, he cautiously concluded that “there are many scenarios that could have played out … the date and circumstances of its last lowering and powering up are totally unknown and would be pure conjecture at this stage.” Even so, like Ryan Harris, he confirmed that “logic dictates that the crew would not have wanted the propeller in place for overwintering and under threatening ice conditions.”

He continued that the discovery “does not necessarily mean that it was used immediately prior to sinking,” which is undoubtedly true. The curious fact that the rudder has been unshipped, argues for the Terror being stationary in Terror Bay before sinking. Yet even if the engine was not used to power into the ship’s final destination in Terror Bay, the fact that the propeller was shipped at all makes it extremely unlikely that the wreck of the Terror is in the same state in which it was deserted in the heavy pack ice off the northwest coast of King William Island on that fateful day in April 1848. As Betts noted, “It is possible the ship was initially beset with a deployed propeller in Victoria Strait, but given the length of time she was trapped by the ice, it is unlikely that the crew would not have found a way to retract the propeller and deploy the strengthening chocks due to the extreme vulnerability of the rudderpost.”

It should be clear that the implications of the ice anchor placement and propeller deployment offer the best, if inconclusive, evidence for the two ships having been remanned after an abortive first attempt to walk to safety. While other potential scenarios cannot be ignored, it strongly supports the contentious historical speculation of a longer Franklin expedition timeline than is generally supposed.

Update June 2025 – Parks Canada has recently updated their site to include a selection of artifacts from the 2023 season – https://parks.canada.ca/lhn-nhs/nu/epaveswrecks/culture/archeologie-archeology/artefacts-artifacts/2023. These include an alternate image of the ice anchor, and revelation that they discovered Erebus’ spare propeller. The ice anchor is there noted as having been found 20m from the wreck vice 27 as above. More illuminating is that in addition to a propeller “mostly buried in sediment and debris at the stern” which they conclude “might have been in its working position when the ship sank,” another was “observed on the seafloor 43 m north of the bow of Erebus.” It was “partly covered by canvas” indicating that it was a spare. This second propeller is obviously a “heavy item” and is actually further from the wrecked hull than the ice anchor, it is more plausible that it “fell from the upper deck prior to or during wrecking” casting doubt on the conclusion that the ice anchor was placed intentionally.

As I noted in a FB post, the TS Robins illustration from 1853 shows a similar ice anchor in position. Looking at it again, it even shows the method of planting the ice anchors in sea ice (at least out on the ice ahead of HMS Assistance). Here the crew have deployed one of the smaller stockless anchors and an ice anchor or grapple out of the hawsepipes, leaving the large bower anchors catted. They are in the process of paying out the other two hawsers and anchoring them to something in the ice (using pickaxes). Anyways, interesting to see if Erebus shows any of these other small anchors paid out around the wreck site! Cheers, Dave! https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/3/32/HMS_Assistance_%281850%29.jpg

Alex,

This is quite a nice pic of Assistance, and shows the ice anchors quite well. Thanks. I would have expected the ice anchors on Erebus to have been deployed in the same classic pattern – from bows and stern – so the location of the one found so far off the starboard side is problematic. It was preferable to dig them into older and stronger ice elements, perhaps there was a pressure ridge in that direction. Everything is speculative and dependent on more evidence, but it is encouraging to see that conversation results from each incremental find.

Dave

Very interesting. There seems to be also a method of tethering the ship to a nearby floe or the land ice using ice anchors, as seen in John Sacheuse’s 1818 work about the Ross Expedition. That might account for a different placement…but what they may have been anchoring to…isn’t there anymore! That and Terror’s propeller (which I am writing a post about, having just added it to my diorama!) certainly raise more questions! https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-137918

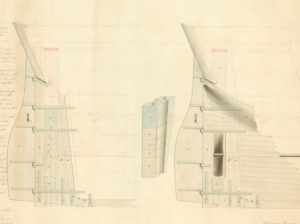

Your post prompted me to modify my model of the wreck site and write my own with some of my research about the RN program of propeller installations: https://warsearcher.com/2025/04/16/propelling-the-terror-modelling-a-lost-franklin-expedition-ships-steampunk-victorian-stern/