Irish-Canadian Franklin Search Expedition, 2004

Report of Field Survey Results

Nunavut Territory Archaeologist Permit No. 04-02A — Class 2

Prepared by:

Charles Moore, M.A.

Maritime Heritage Consulting-2004

Executive Summary

This project aimed to locate a ship lost on Sir John Franklin’s final expedition of 1845, continuing field research commenced in 1992 and further pursued during the field seasons of 1993, 1997, 2000, 2001 and 2002. The rationale behind searching the areas off the Adelaide Peninsula (Utjulik) is based primarily on traditional Inuit knowledge. Field research methodology consisted of dropping a multi-imaging sonar unit beneath the ice in target areas identified through analysis of data collected by magnetometer on previous surveys. No ship remains or other cultural material were evident from the sonar searches. A fragment of small boat on land was an incidental discovery. This boat had been abandoned within the last 40 years. Activities were digitally recorded by a documentary film crew.

Duration of Field Work: May 11 to May 21, 2004.

Field operations consisted of checking magnetometer targets in two areas to the west of the Adelaide Peninsula.

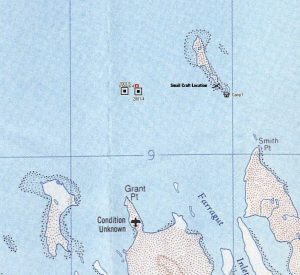

Northern Survey Area: About 6km north of Grant Point within a box defined by

N 68.466 W 98.677 and N 68.463 W 98.655.

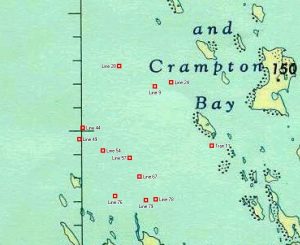

Southern Survey Area: Between 3 and 13 kilometers north and east of O’Reilly Island within a box defined by N 68.214 W 99.004 and N 68.118 W 98.748.

All locational information in this report is listed in latitude and longitude, degrees and decimal degrees, NAD 83.

Field Personnel:

Kevin Cronin (Principal Sponsor)

David Woodman (Sponsor, Historian, Search Coordinator, Diver)

John Murray (Sponsor, Cameraman, Diver)

Peter Bate (Film Director)

Jon Woods (Sound Technician, Camera Assistant)

Saul Aksalook (Principal Guide)

Darryl Kovtek (Guide)

David Siksik (Guide)

Colin Putugaq (Guide)

Tom Gross (Camp Logistical Coordinator)

David Holland (Dive Master, Sonar Technician)

Rob Field (Assistant Archaeologist, Diver)

Charles Moore (Archaeologist, Permit holder, Diver)

Acknowledgements

The 2004 expedition was primarily sponsored by private funds. The principal contributor was Kevin Cronin, but funds were also supplied by David Woodman and John Murray. Further financial and administrative support was provided by the Vancouver Maritime Museum and the Royal Canadian Geographical Society. In-kind contributions were graciously extended by Roger Sabourin of AquaLung Canada; Brad Herman, owner of Colt Creek Diving; Dave Stewart, owner of DASCO Equipment Inc; Dan Orr of Divers Alert Network; Ken McMillan of McQuest Marine Geophysical Services; and Frank White of Whites Manufacturing. Many thanks are also due to Constable Mike Toohey of Gjoa Haven RCMP detachment.

The expedition would not have been possible without the stalwart volunteer contributions of Tom Gross and David Holland. This was the seventh expedition for Tom Gross in Captain Woodman’s company, and the third for Saul Aksoolak. Dave Holland, John Murray, and Kevin Cronin were each involved in one previous expedition, while Peter Bate, Jon Woods, Rob Field and Charles Moore were working in the Arctic for the first time.

Introduction

Searching for any sign of HM Ships Erebus and Terror has been at the forefront of many expeditions over the last 150 years. Yet, while lying at the heart of the Franklin Expedition’s failure to navigate the elusive North-West Passage, the ultimate circumstances surrounding the ships’ loss remains a mystery.

Public interest in what is known of the Franklin disaster is reflected in the designation of Sir John Franklin as a Person of National Historic Significance, along with two related National Historic Sites (NHS) in Nunavut (the Beechey Island NHS, and the Erebus and Terror NHS, Erebus Bay). While historical research is unlikely to offer much new information, archaeological research has a demonstrated potential to yield exciting data with a clear benefit to public education. For example, the Franklin graves at Beechey Island NHS have been subject to detailed archaeological investigations by Owen Beattie and his colleagues with interesting and well-publicized results (Beattie and Geiger 1987). Just as terrestrial cultural resources in the Arctic may be remarkably well preserved and rich in scientific data, so submerged cultural resources in the isolated underwater environment of the Arctic may be exceptionally rich in material for scientific research and public education.

Both Erebus and Terror were converted Royal Navy bomb vessels. They represent a type of ship type that made a critical contribution to polar exploration over the span of a century, between 1741 and 1845. The “bombs” were robustly built in order to mount heavy mortars used to bombard coastal installations and port cities. Vulnerable to attack by other ships, they tended to use the cover of night to move within range of the their targets. The Royal Navy bombs were typically named after volcanoes (eg: Hecla, Aetna, Vesuvius), or denizens of a fiery underworld (Beelzebub, Fury, Erebus[1]) alluding to their appearance at night as they blasted their mortar bombs, and incendiary “carcasses” into a high trajectory. The choice of name also underlined their usefulness as weapons of psychological terror. While the bombs’ indifferent sailing qualities and minimal accommodation space made them poor cruisers in the years between wars, with their mortars and magazines removed, their hefty scantlings made them the best of the larger ships used for polar exploration. They became the vessel type preferred by Middleton, Parry, Back, and Ross for exploring north and south polar seas, just as converted Whitby colliers of similar size were preferred by Cook and Vancouver for contemporary explorations in the Pacific. No bomb vessel has survived. Three of the eight Royal Navy bombs used in polar exploration were wrecked in that capacity, all in the Canadian Arctic.[2] HMS Fury was ground to a pulp by the ice over the rocks of the Somerset Island beach that bears its name. And one ship, either HMS Terror or Erebus, was probably crushed in the ice off Cape Frances Crozier, its remains scattered beneath a permanently advancing cover of ice. If the other of Franklin’s two vessels survived long enough to sink in relatively benign circumstances off Utjulik, it would provide a unique archaeological opportunity to study a type of vessel that had contributed so much to polar exploration in the age of sail. Both Terror and Erebus are of additional interest because they employed some cutting edge technology for the period, including built-in water tanks, diagonal iron bracing (Erebus), central heating systems,[3] ice-reinforced bows,[4] and auxiliary screw propulsion.[5]

Research Background

The search areas for this project were defined by Woodman and are based on intelligence gleaned from the Inuit first by Leopold McClintock in 1859, later by Charles Frances Hall, and with greatest detail by the Schwatka expedition in 1879 (Woodman 1991: 248-269; 2003). The interpretation Woodman presents is that one of the two vessels in the Franklin expedition survived a minimum of three winters in the pack ice of Victoria Strait, before being finally released into the Queen Maud Gulf. Probably under the direction of a skeleton crew by this time, it was maneuvered to, and perhaps anchored at, the location where it was ultimately observed by the Neitchille Inuit in smooth year-ice near an island off the north-west shore of the Adelaide Peninsula (Utjulik). It sank there with a minimum of violence, possibly the result of a botched salvage attempt, in water sufficiently shallow that the tops of the masts were visible (suggesting a depth of less than 130 ft./40m).[6] There is some ambiguity in the accounts suggesting either that this location was off Grant Point (northern search area) or the island currently identified as O’Reilly Island (southern search area). The total search area represents some 300km2.

Captain Woodman began his investigations in these areas in 1992 with an airborne magnetometer search that identified 61 magnetic anomalies (Woodman 1992). The most promising of these three targets were investigated in 1993 with through-ice sidescan sonar, but without result. Sea-borne surveys in 1997 and 2000 employed side-scan and forward-looking sonar as well as magnetometer, but due to wind and seas over the short summer seasons only about 80km2 were covered (Woodman 1997; Bertulli 1998; Grenier and Harris 2004; Delgado 2000).[7] In contrast, 11 days of sled-borne magnetometer work in 2001 covered all of the Grant Point survey area, approximately 166km2, with a line spacing of 200m (Woodman 2001). In 2002, a second sled-borne magnetometer survey produced a higher resolution (50m) pattern in the vicinity of targets identified in the previous year and surveyed at a 200m-spacing the O’Reilly Island search area (Woodman 2002).[8]

The surveys by boat and through the ice confirmed that the underwater environment was generally a featureless plain averaging 72 ft. (22m) in depth in the northern search area and 89 ft. (27m) in the southern area.[9] Notably absent were any signs of ice scour on the seabed. This welcome news meant that a wreck site located here might avoid impact by heavy ice, raising the possibility that the local environment could potentially preserve a wreck in a condition similar to the Breadalbane (1853) that was found largely intact and upright with two masts still standing in about 300 ft. (100m) of water off Beechey Island (MacInnes 1985).

Over a decade of searching off Utjulik all of the high priority magnetometer targets identified in 1992 were found to be geological in origin. Others have been identified and analysis of the accumulated magnetometer data prior to the 2004 season identified three high priority targets remaining in the Grant Point search area and four off. O’Reilly Island. The 2004 expedition would focus on these targets.

Methodology and Objectives

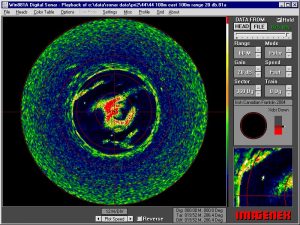

The approach to investigating the magnetometer targets was to begin with relocating each target by GPS.[10] At each location, a 16cm hole was to be drilled allowing for an echo sounder and a sonar unit[11] to be lowered through.

These preliminary sensors would provide an idea of the depth, general bottom topography and indications of a potential wreck site. If the preliminary results were positive the intention was to cut a slightly larger hole to allow for the lowering of an ROV[12] mounting a camera and a sonar unit.

It was suggested in the permit application the ROV might be the primary tool for the project. If the ROV in turn produced positive sonar and visual results then the next level of investigation would be by divers on SCUBA through a substantially enlarged hole through the ice.

The potential of diving on an archaeological site complicated the permitting process. Although there was never any intention to collect artifacts or samples from the site, according to Nunavut Site Regulations, a Class 2 permit is required for diving operations approaching within 30m of a site.[13] It would be necessary to approach within this distance to visually confirm sonar results and undertake any site identification or assessment. Because of the proposed diving operations and the recognized significance of the site, 17 project-specific conditions had to be met as a requirement of permit issuance, including staying 3 metres away from any submerged cultural feature or site. Research objectives were effectively limited to search and site identification, and restrained production of documentary footage.

The only other shipwreck incident reported in the area is a barge that sank in 1926 to the west of O’Reilly Island (Woodman 2003: 8).[14] Although probably an old sailing vessel, identifying the remains of this barge in contrast to a bomb vessel should be straightforward with visual access. It is generally thought that because Terror and Erebus were ships of the same type they were, therefore, practically identical, especially after their refits for polar service. This would make identification between these two vessels difficult. Terror was laid down to the Vesuvius Class specifications in 1812, while Erebus was launched in 1826 to the Hecla Class specifications of 1813. One difference between classes was the smaller as-built dimensions of the Vesuvius group, leaving Terror with about 1.83 ft. (0.56m) less breadth and 2.67 ft. (0.81m) less length than Erebus (Ware 1994:67-68). Easier to determine from a survey required to stay 3 metres away from the wreck were a number of diagnostic characteristics that may be discerned from two sets of as-fitted plans. One set is labeled “Terror and Erebus” (which adds to the perception that the ships are indistinguishable), however, these 1839 plans are actually of Erebus, as several notes and sketched features indicate different arrangements on Terror. On the other hand, the set of 1837 (as fitted for 1836 with 1845 modifications for power drawn over) plans attributed to Terror are certainly of that vessel, and reveal a number of readily distinguished features from the 1839 plan set.[15]

Diagnostic features based on comparison of the two as-fitted plan sets that might be useful in identifying the two vessels in a survey relying on distant visual data include 22 characteristics visible on deck. For example, quarterdeck housings, pump type, number and location, fore hatch locations, types of waist bulwark, davit and knight placements are quite distinctive. There are also seven topside characteristics visible, most conspicuously the continuous channel blister found on Erebus. If the wreck were opened up, another seven diagnostic characteristics are apparent from the lower, orlop, and hold levels, including location and types of furnace and water tank arrangements. Even if only the major timbers remain, five diagnostic characteristics related to scantlings including the angle of the sternpost to keel, and the 2 pair of futtock riders installed only on the Terror, may be identifiable (see Appendix C).

In the course of fieldwork, no vessel or debris was found and no identification was necessary. In fact, no diving operations were undertaken, whether with ROV or divers, to provide any visual data. Given the minimal bathymetric relief, multiple hole coverage around each target, and quality of accoustic data from each hole, it was determined that results from the through-ice sonar survey were adequate to establish with reasonable certainty that no wreckage was present on the seabed in the vicinity of the magnetometer target locations investigated. Geological sources for the magnetic anomalies may be assumed, and at some target locations minor geological features were visible at or very near the datum. The through-ice sector sonar results were also judged sufficient so that no additional detailed magnetometer work was performed on this expedition.

Survey Results

Field work took place between May 11 and May 21. The entire survey area was covered in ice measuring approximately 2 meters thick. Target areas were accessed by snowmobiles towing sleds. No survey days were lost due to weather. Daytime temperatures ranged from –20C to 4C with winds generally moderate. Auger holes drilled through the ice were 16cm in diameter, which were large enough to take the sounding lead as well as the sonar housing mounted on the end of a PVC pipe extension.

Seven magnetometer targets were classified as “priority one” based on the magnetic characteristics exhibited. These, along with an additional eight targets of lower priority but all within the specified search areas, were investigated. Four of the total number of targets proved to be located in shallow water, less than 30 ft. (9.1m), so investigations at these locations were limited to taking soundings. All 15 of the magnetometer targets were located and holes cut through the ice to take soundings between May 11 and 13. No sonar data was collected prior to the arrival of the archaeologists (May 15).

The typical procedure for investigation around a magnetometer target in a suitable depth was to auger a hole at the centre of the anomaly. This location would become the datum for each search pattern, with four additional holes typically being set out from the datum at a distance of 100m along the four principal cardinal points, due north, east, south, and west, respectively. For some areas of less interest fewer holes were used.

Sonar data was collected at various range settings between 30 and 200 metres from each location into which the sonar transducer was lowered.[16] If anything of potential interest showed in close proximity to the sensor location, an additional survey hole, typically 50m distant, might be drilled.

Data collection in the search areas consisted solely of through-ice sonar readings and hand soundings taken from each hole with a line measuring 80 ft. (24.5m) in length. Depths in excess of this were estimated from sonar readings.[17] Magnetometer targets in the northern area were searched first. The through-ice sonar data were entirely negative with respect to indications of cultural material and were considered of sufficient quality in terms of technology, methodology, and bottom conditions so that no efforts were taken in deploying other search tools.

Northern Search Area

Three magnetometer targets were investigated off Grant Point. Around these targets a total of 14 holes were drilled through the ice with soundings ranging from 70 to about 90 feet (23 – 29m) in depth (see Table 1 for summary). The digital multi-imaging sonar indicated a relatively flat bottom marked by a series of low relief ridges running in a roughly NW/SE orientation, and nothing suggestive of ship remains.

Table1: Magnetometer targets investigated in the northern (Grant Point) search area. Priority assessment was based on magnetic characteristics.

| Target Name | Priority | Latitude | Longitude | Number of test holes | Ave. Water Depth (Ft.) |

| Pattern 4 | 1 | 68.46574 | -98.65726 | 6 | 73 |

| N-2 | 1 | 68.46326 | -98.65565 | 4 | 76.8 |

| N-3 | 1 | 68.46378 | -98.67628 | 4 | +/- 90 |

Southern Search Area

Twelve magnetometer targets were investigated in the southern area, where an additional 45 holes were drilled with soundings ranging from 6 to about 170 feet (2 – 55m) in depth (see Table 2 for summary). Where the depths were greater than 30 ft. (9m), the approximate depth of the Erebus from keel bottom to gunwale top, the sonar unit was deployed. Images taken from 39 holes in eight target areas showed stones and small boulders on a relatively flat bottom marked by ridges similar to those noted farther north, but nothing suggestive of ship remains.

| Target Name | Priority | Latitude | Longitude | Number of test holes | Ave. Water Depth (Ft.) |

| Line 28 | 1 | 68.213547 | -98.927048 | 5 | +/- 170 |

| Line 24 | 1 | 68.20182 | -98.82653 | 3 | 12.5[20] |

| Line 57 | 1 | 68.148285 | -98.907211 | 5 | 64.6 |

| Line 78 | 1 | 68.118362 | -98.875938 | 1 | Shoal |

| Line 9 | 2 | 68.198929 | -98.858727 | 5 | 77.2 |

| Line 44 | 2 | 68.169823 | -98.997543 | 5 | +/- 85 |

| Line 76 | 2 | 68.120926 | -98.935295 | 6 | 59 |

| Line 79 | 2 | 68.117699 | -98.875732 | 1 | Shoal |

| Trans 11 | 2 | 68.156639 | -98.748825 | 0 | Shoal[21] |

| Line 49 | 3 | 68.161682 | -99.003601 | 3 | +/- 130 |

| Line 54 | 3 | 68.153419 | -98.958733 | 5 | 76.2 |

| Line 67 | 3 | 68.134903 | -98.888885 | 5 | 55.6 |

Conclusion and Recommendations

At the end of field work for 2004, there is still no sign of any ship remains underwater off Utjulik. The magnetic anomalies investigated were evidently all geological in origin.

New sonar data confirms seabed composition and form. It appears to consist entirely of gravels and cobbles with occasional small boulders. Relief is very low. In this environment there is nothing to mask the presence of cultural material standing proud of the seabed and no soft sediments for burial. For these reasons and thanks to the repeated overlapping of sonar images we can be confident in the negative results of the sonar data.

The nature of the seabed relates to the report that one or more of the ship’s masts were visible after sinking. Only one of the magnetometer targets was in water too deep for the top of the main mast on Erebus to have shown. The minimal slope evident everywhere on the surveyed seabed suggests the ship should not have settled with a list much more than would naturally be indicated by the depth of its keel and hull deadrise. In the case of the Erebus, the angle of heel would not exceed 10 degrees, or an insufficient amount to significantly reduce the height of the masts.

There is also good reason to expect any shipwreck within the survey area to have maintained a three-dimensional aspect. Other known saltwater shipwrecks in Nunavut, the Breadalbane, located in deep water 700km north of Utjulik, and James Knight’s ships, Albany and Discovery (1720), located in shallow water off Marble Island at a latitude approximately the same distance south of Utjulik, are three-dimensional and exhibit excellent levels of organic preservation. Both of these wreck sites have been protected from moving ice damage by depth and protective landforms, respectively. Within the Utjulik survey areas, no evidence of ice scour on the seabed has been encountered, which argues convincingly for similar protection from moving ice.

The fact that the magnetometer data have not led to the discovery of a shipwreck does not necessarily indicate that there is no shipwreck within the area surveyed by magnetometer. In contrast to the flat, sonar-friendly seabed, the local magnetic background is very “noisy” with considerable potential of masking metal concentrations. It is also possible that local environmental conditions are particularly poor with respect to iron preservation. Only negative sonar data can be taken with confidence to indicate the absence of a shipwreck over substantial areas of the seabed off Utjulik, especially given that substantive articulated remains might be anticipated.

In the northern search area, about 80km2 of the seabed has been covered by side-scan and forward-looking sonar. The area that “best fits” with the historic record in this area clearly has no shipwreck in it, however, this does not mean that an expanded search of the northern search area, as may be defined by water depths and other factors, is not warranted.

Following the 2004 season only about the 1.38km2 of the southern search area have been surveyed by sonar[22] and over 150km2 of seabed remains to be investigated. Based on past rates of survey by boat this should take about four seasons to complete. However, both the accumulated archaeological data and oral testimony seem to increasingly point to this area northeast of O’Reilly Island as the most likely location of the wreck, making continued search efforts there worthwhile.

Further information obtained in 2004 from Inuit sources indicated that the islet dubbed “skull islet”, after a skull thought to be European was discovered there on the 1997 expedition, is the location known as “Ook-soo-see-too”, where footprints of Franklin crewmen were seen in the snow by contemporaries. A tent site and optical prism were also found there in 2002. Approximately 8km to the east of “Ook-soo-see-too”, on the Adelaide Peninsula near the entrance to Sherman Inlet, a “large stick” was found approximately eight years ago by a hunter (now deceased). This surface find has been seen by Saul Aksalook from whose 2002 description it is apparent that the “stick” may be a fragment of mast or other substantial spar. A one-day search for it was conducted during the 2002 expedition, which was unsuccessful probably due to snow cover. Another search in 2004 was not attempted owing to similar snow conditions, but the presence of the possible spar was independently corroborated by various informants, albeit with second-hand knowledge. The distribution of these finds along with other potentially ship-related artifacts, including the spike with a broad arrow found in 1965, the copper, belaying pin, barrel staves, and “other evidence of a nearby wreck” found in 1967, and the wood, copper sheet, and pot bottom found in 1997, seem to point to a source within the southern part of Wilmot and Crampton Bay, to the north and/or east of O’Reilly Island.

It is remarkable that finds apparently related to one of Franklin’s ships are still being found along the shores of this area. The validity of the apparent distribution pattern should be tested with walking searches in the summer months of local areas where historic artifacts, remains, or features have not yet been located. These should focus on the western shores of O’Reilly Island and those islands immediately to the north of it, especially the one at the northern end of the chain where camp #2 was located in 2004. In addition to the relocating the supposed spar fragment, the mainland shores either side of the entrance to Sherman Inlet should be searched, as should any parts of the island chain to the north and east of skull Islet that have not been walked yet. Correlating the resulting pattern with prevailing current and wind directions in the summer months should indicate the high priority areas for further work with side-scan or forward-looking sonar.

Another method to reduce the area covered by vessel-born sonar would be to begin with a contour-based survey of shallower water immediately north of O’Reilly Island. There is no point in surveying water less than 30 ft. (9.1m) because this approximates the height of the bulwarks on a bomb vessel. The priority should also be placed on surveying water deep enough to be free of ice-impact. Determining if this boundary is deeper than 30 ft. by sonar, and diver or ROV and defining this line around shoal waters within the search area would help delimit the area more usefully covered in swaths. Establishing the basic bathymetry of the search area will also help define the deeper limits of the search area along the 130 ft. (40m) contour.

Archaeological data collected to date off Utjulik remain incomplete with respect to testing the hypothesis that one of Franklin’s ships sank in either the southern or northern search areas. The debris found on land in the vicinity of O’Reilly Island may suggest the presence of submerged wreckage but it may be from the barge lost to the west of O’Reilly Island in 1926, or be material that may have drifted in from other ships wrecked to the north. The potential remains for gathering field data from land and underwater that will both assist further search directed at a Franklin vessel, or reveal other submerged cultural resources.

References

Beardsley, M.

2002 Deadly Winter: The Life of Sir John Franklin. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD.

Beattie, O. and J. Geiger

1987 Frozen in Time: Unlocking the Mystery of the Franklin Expedition. Western Producer Prairie Books, Saskatoon.

Bertulli, M.

- Survey of Cape Felix, King William Island, June 1995. Archaeologist Permit 95-797, report submitted to the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, Yellowknife.

- Archeological Investigations around O’Reilly Island, Northwest Territories, August 1997. Archaeologist Permit 97-858, report submitted to the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, Yellowknife.

Delgado, J.P.

1999 Across the Top of the World: the Quest for the Northwest Passage. Douglas and McIntyre, Vancouver.

2000 Final Report: Non-Intrusive Sonar Survey of Arctic Archaeological Sites. Archaeologist Permit 00-008, report submitted to the Nunavut Department of Culture and Heritage, Igloolik.

Graham, G.S.

1958 The Transition from Paddle-Wheel to Screw Propellor. Mariner’s Mirror 44: 35-48.

Grenier, R. and R. Harris

2004 Final Report and Analysis of Archeological Material Recovered from the Vicinity of O’Reilly Island, Northwest Territories, August 1997. Archaeologist Permit 97-858, ms. report to be submitted to the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, Yellowknife.

Henderson, L.

1992 HMS Terror and Erebus, Agenda Paper 1992-52. Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada.

Kowal, W.

- Final Report Project Supunger. Archaeologist Permit 94-778, report submitted to the Prince of Wales Northern Heritage Centre, Yellowknife.

Lyon, D.

1980 Steam, Steel and Torpedoes: the Warship in the 19th Century. National Maritime Museum, The Ship, vol. 8, B. Greenhill, general editor. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office, London.

MacInnis, J.

1985 The Search for the Breadalbane. David and Charles, London.

Mondfeld, W.

1989 Historic Ship Models. Sterling Publishing, New York.

Smith, E.C.

1937 A Short History of Naval and Marine Engineering. Babcox and Wilcox, Cambridge.

Ware, C.

1994 The Bomb Vessel: Shore Bombardment Ships of the Age of Sail. Conway Maritime Press, London.

Woodman, D.C.

1988 Arrangements and Orders. Ms. in author’s files.

1991 Unravelling the Franklin Mystery. McGill-Queen’s University Press, Toronto.

- “Project Ootjoolik,” Sentinel, 29.2 (April-May): 28-29.

- Eco-Nova 1997. in author’s files.

2001 Utjulik 2001 Expedition Report. Nunavut Scientific Research Permit # 0400501R-M, report submitted to the Nunavut Research Insititute, Iqaluit.

- Irish-Canadian Franklin Search Expedition Report (2002). Nunavut Scientific Research Permit #0400602R-M, report submitted to the Nunavut Research Institute, Iqaluit.

- The Utjulik Wreck. Ms. in author’s files.

[1] Erebus is personified in Hesiod (Theog. 123 cited in Encyclopedia Britannica 1959 5:681) as the “son of chaos, brother and husband of night….” HMS Erebus was the first bomb to bear this name, while Franklin’s Terror was the fifth bomb of that name; the first belonging to the original Blast class of 1695 (Ware 1994).

[2] The first bomb vessel used in Arctic exploration was Furnace, used by Christopher Middleton in 1741-42. Others include Racehorse and Carcass under Constantine Phipps (1773); Hecla under Edward Parry (1819-20, 1821-23, 1824-25); Fury, also Parry (1821-23, 1824-25); Terror was captained by George Back in 1836-37; and James Clark Ross took Erebus and Terror to the Antarctic in 1839-41. None were used following John Franklin’s 1845 expedition (Delgado 1999: 52-53, 55, 58-64, 73-77, 84-88, 103-105, 109; Ware 1994: 92-104).

[3] According to as-fitted plans, the Erebus had a “Sylvester’s patent” furnace located in the main hold that warmed air distributed through ducts in the lower deck area. The distribution system illustrated on the plans for the Terror (1837) uses small diameter pipe to heat the same area, presumably for water or steam heated in a furnace located on the Orlop deck forward beneath the galley. As this system had not proven popular with Back and his crew in 1836, it may have been upgraded with the type used on Erebus (Woodman 1988: np).

[4] The bows were sheathed with iron for the 1845 voyage (Woodman 1988: np). Additional reinforcement indicated on plans includes solid timbering inside the bow and possibly a watertight bulkhead (Ware 1994: 100).

[5] The British Admiralty had shown no interest in the demonstration by Swedish-American designer John Ericsson of a screw-driven vessel in 1837 (Graham 1958: 39-40). It is notable that Erebus and Terror were towed out of the Thames by Rattler, the first screw-driven vessel in the Royal Navy which that same year (1845) was to win a famous “tug-of-war” with her side-wheel sister ship Alecto (Lyon 1980:18; Beardsley 2002:196). By 1850 there were about 50 propellers in the Royal Navy (Smith 1937: 75).

[6] Height of the mainmast, keel to truck, on HMS Erebus may be estimated at approximately 130 ft. (40m). The foremast total height was approximately 121 ft. (37m). If the main topgallant mast were struck then the height would be approximately 110 ft. (34m), and if both the topgallant mast and topmast were struck the height would have been only 70 ft. (21m). Because HMS Terror had approximately 6% (1.83 ft.) less beam than Erebus, the mast heights may be reduced proportionally for that vessel. Calculations are based on the mast and spar dimensions for the bomb vessel Carcass (1757) in Ware (1994: 84, 86) and general calculations of mast height proportional to beam for early 19th-century British warships (ie: Mondfeld 1989: 216-17).

[7] In the summer of 1997, data was gathered from two launches from the Canadian Coastguard icebreaker Laurier over four days. In 2000, the RCMP vessel Nadon during its transit of the Northwest Passage, spent five days using forward-looking sonar.

[8] In addition to survey results on the water, expeditions since 1992 also encountered material on land thought to be remains of the Franklin expedition. In 1997 copper artifacts and Caucasian male skull were found on an unnamed island near O’Reilly (Woodman 1997; Bertulli 1998; Grenier ??). In 2001, three large rectangular tent sites and a prism from an optical device were found near the skull (Woodman 2001). Expeditions were organized by Woodman to search for Franklin material on land in 1994 (Kowal 1996), and 1995 (Bertulli 1995).

[9] Water depths in the northern and southern search areas were not surveyed in detail by the Canadian Hydrographic Service and only a few soundings are apparent on CHS charts 7083 and 7731.

[10] Hand-held units provided the GPS data with an anticipated accuracy of between 5 and 8 metres. Experience in the field returning to marked targets yielded repeatable results of better than +/- 2 metres.

[11] An Imagenex 881A digital multi imaging sonar unit.

[12] The ROV (Remotely Operated Vehicle) taken on the expedition in 2004 was a VideoRay 2002, a lightweight vehicle measuring 30.5 x 22.5cm and weighing only 3.6kg.

[13] Nunavut Archaeological and Palaeontological Sites Regulations 5.(2): “No person, other than a person engaged in a search and rescue operation, shall dive, or approach with an underwater submersible, to within 30 m of an archaeological artifact without a Class 2 permit.”

[14] Oral testimony of this event was confirmed in discussions with Inuit respondents in 2004 (David Woodman, personal communication 2004).

[15] Both sets of plans consist of five sheets, showing profile, upper (weather), lower, and orlop deck plans, and midship section. Part of the National Maritime Museum collection, all but one of the sheets are reproduced in Ware (1994: 100-104), although the set of plans attributed to Terror and Erebus are mislabeled in the captions as “1836, as fitted”. Confirming some of the differences is an additional set of as-built (1826) plans of Erebus, also from the National Maritime Museum collection and reproduced in Ware (1994: 71-73).

[16] Sonar gain settings were typically 20 db for 100 to 150m ranges, 15 db for 50m, 12 db for 40m, 10 db for 30m, etc.

[17] No corrections for tide levels were made in the soundings. The maximum tidal range in Cambridge Bay (Stn 6240) during field work was 1.3 ft. (.58m).

[18] A radar reflector housed in a plastic cylinder and normally used by small craft.

[19] Targets N-2 and N-3 were formerly referred to as 2001-4 and 2001-5, respectively.

[20] Although the initial sounding at Line 24 was shoal (10’), its location (in good agreement with the Inuit testimony) and magnetic priority justified a revisit by a secondary survey team led by Rob Field. Two further sounding holes were drilled nearby to confirm that the sounding was correct and consistent with the surrounding area.

[21] The magnetic anomaly at Trans 11 was found on investigation to lie directly in line with a reef complex, and was covered by a pressure ridge of ice, forced up by this reef, to a height of approximately 3 m. No soundings were taken here as in the opinion of the guides and surveyors it was obviously shoal.

[22] Based on approximately 0.125km2 per target area investigated by sector sonar in 2004.