Puhtoorak, Position and Pronouns

There are many accounts in the nineteenth-century Inuit remembrances of Inuit visits to the ships of the Franklin expedition. These can be divided into two groups, those of visits to the ships and meeting with living crew and those of visits to abandoned ships. The former relate to a ship (or sometimes ships) to the west of King William Island, and it is told how this ship sank quickly in deep water, with little benefit to the later Inuit from recovered wealth of wood and metal. The Inuk Kokleeargnun told C.F. Hall a detailed remembrance of a visit to the ships that is often questioned as a conflation or misremembering of a visit to John Ross’ Victory rather than to the Erebus and Terror.

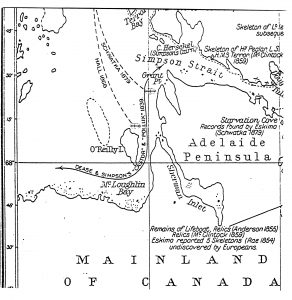

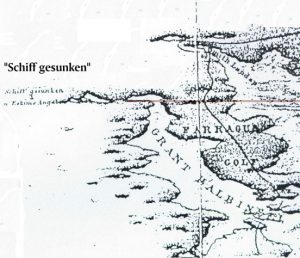

The other ship, now known to be HMS Erebus, was found far to the south in the region of Ugjulik, a large area to the west of the Adelaide Peninsula encompassing Wilmot and Crampton Bay. In this expansive region two locations were identified, the northern one near Grant Point and a southern one nearer O’Reilly Island. As there was only one wreck in the area it was assumed that one of these locations was correct – but which one?

The clues for each location were not straightforward. Most of the remembrances of the wreck site were second- and third-hand retellings of events of which the narrator had no personal experience. An exception is the account of the only person to have specifically claimed to have visited the Franklin ship, when unmanned. This was the Inuk hunter Puhtoorak, who relayed his story to members of the Schwatka expedition (1878-9). Schwatka considered that “[t]he old man, then about sixty years old, had an intelligent, open face, and all his answers were given without hesitation, in a straightforward manner which carried the conviction of truth.” Schwatka and his companions elicited details of this wreck in very detailed transcriptions of the interview with Puhtoorak which are generally confirmed by the accounts of other natives. The most complete version, given by Schwatka himself, follows:

“On the 16th, Col Gilder + I had a most satisfactory interview with Ikkinnilik Puhtoorok, the head man, Ebierbing acting as interpreter.

… he saw a white man was a dead one in a large ship about eight miles off Grant Point. The body was in a bunk inside the ship in the back part. The ship had four big sticks one pointing out and the other three standing up. On the mainland near Smith Pt. + Grant Pt. he saw the tracks of white men and judged they were hunting for deer. The first time he saw the tracks of four white men and afterwards the tracks of three. He saw the ship in the spring before the spring snow falls and the tracks in the fresh spring snow when the young reindeer come of the same year. He never saw the white men. He thinks that the white men lived in this ship until fall and then moved onto the mainland. They did not understand how to get into the ship so they cut through one side and when the ice melted in the summer she sank as the water poured in.

After the ship sank they found a small boat on the main-land in Wilmot Bay. When he went on board the ship he saw a pile of dirt on one side of the cabin door showing that some white man had recently swept the cabin. He found on board the ship four red tin cans filled with meat and many that had been opened. The meat was full of fat. The natives went all over and through the ship and found also many empty casks. They found iron chains and anchors on deck, and spoons, knives, forks, tin plates, china plates etc below. When the ship sank her masts stuck out of water and many things floated on shore which the natives picked up. He also saw books on board the ship but the natives did not take them. He afterwards saw some that had washed ashore. He never saw any stone monument or cairn on the mainland near where the ship sank. There was one small boat hanging from the davits which the natives cut down. Some of the ship’s sails were set.”

The specificity as to the location of the wreck “eight miles west of Grant Point” seemed definitive. Schwatka’s companion. Klutschak also recalled that the Inuit also found “a small boat in Wilmot Bay which, however, might have drifted to that spot after the ship sank. The credibility of these reports was later enhanced when confirmed by similar statements by others.” As this implied that the ship did not significantly drift the assumption was that the eventual wreck would be found nearby, and a chart drawn by the expedition to show the location is consistent with this.

All of the accounts by Schwatka, Gilder and Klutschak were in general agreement. Contemporary identification of the nearby islands named Umiartalik (“here is a boat”) as the location where a lifeboat had been found, while nearby Aviumavik island survives as the location where traces of white men were seen. Largely based on these clues, reinforced by a latitude and longitude recorded by Hall, Puhtoorak’s account inspired years of survey of those waters, without result.

In fact the wreck was found in 2014 about twenty four kilometers (fifteen miles) south of this indicated location. In a search area of hundreds of square miles it was generally accepted that this minor error was insignificant. and confirmed that Puhtoorak was generally correct, if indeed he misidentified the exact spot where the ship sank. The more generous commentators concluded that he had been misinterpreted, and pointed out that other informants had placed the wreck to the northeast of O’Reilly Island. The discovery roughly half-way between the two named points was a considered a triumph of Inuit accuracy.

Yet I worried about the Puhtoorak account. He had been most confident in his tale. Knowing that Inuit geographical accuracy when discussing events in their land was a literal matter of survival gave me doubts about even this small inaccuracy. After the discovery I was sitting on a park bench with Marc-Andre Bernier, the head of the Parks Canada Underwater Archaeology Team that had found the wreck. I bemoaned the fact that Puhtoorak had seduced searchers astray and delayed the discovery for a decade. He then remarked that this was not necessarily true – perhaps Puhtoorak had visited the ship near Grant Point, but the wreck had subsequently moved, drifting or manned, to its wreck location further south. I initially felt that he was kindly trying to assuage my own disappointment in having focussed the effort of my teams to the wrong area, but on return home I started to seriously consider his idea. This required a revisit of the Puhtoorak text itself with a more critical eye.

The first thing to be addressed was a troublesome comment recorded by Schwatka’s companion Klutschak, and him alone, that, although the ship had been visited twice it remained “in the same position.” This seemed to imply that the ship had sunk in place at the location it was originally found, and was a seeming refutation of Marc-Andre’s idea. A more rigorous reading of the relative chronology of Puhtoorak’s visit showed a possible way out of this difficulty. We can see his chronology, he “saw the ship in the spring before the spring snow falls and the tracks in the fresh spring snow when the young reindeer come of the same year.” He thought that there were white men still living in the ship at this time “until fall,” and that they then moved onto the mainland. He freely admitted that this was solely conjecture as “he never saw the white men” himself, only their tracks in the snow. The Inuit in his party apparently did not approach the ship until he later entered the intact but abandoned ship. He specifically also dates these actions to the spring. This timing is entirely consistent with Klutschak’s comment that “on their first visit the people thought they saw whites on board; from the tracks in the snow they concluded there were four of them. This was in the fall; the following spring they visited the spot again and found the ship in the same position.” (emphasis added).

The remembrances of the seasons of each event seems illustrative. By combining the parts of Puhtoorak’s story using the first-person pronoun, what he personally claims to have witnessed and done as opposed to what he surmised or was done by others, we get a clearer picture. Schwatka recalled that Puhtoorak “saw the ship in the spring before the spring snow falls” and the white men’s tracks “in the fresh spring snow of the same year.” Gilder agreed that the “first party” found the ship “in the spring before the spring snow falls.” His version confirms that the tracks were later found “when the spring snows were falling … in the fresh spring snow when the young reindeer come of the same year.” Klutschak remembered the discovery of the ship as “in the fall” but he was probably mishearing Puhtoorak’s statement, recorded by Schwatka, that white men were still living in the ship “until fall.” He then confirms that “the following spring they visited the spot again and found the ship in the same position.” In this reading the “same position” is quite straightforward and refers to the original sighting one spring, and the visit to the abandoned ship the next. I had been reading the “same position” as that in which the shipwreck had been found, but I now began to see that this was perhaps an unfounded inference, perhaps the manned ship had been seen one spring, and the abandoned ship was visited a year later.

One notable aspect of Puhtoorak’s account is that there is no reference to the actual wreck of that ship, only to its mechanism, that “[t]hey did not understand how to get into the ship so they cut through one side and when the ice melted in the summer she sank as the water poured in” and the aftermath “her masts stuck out of water.” In neither statement did he specifically indicate himself as a witness, was “they” inclusive and could be read as “we,” or exclusive, indicating that he was retelling the accounts of others? With a more critical eye I started to see that Puhtoorak’s statement was not a simple account of first-hand experience, but a melding of these with those of other hunters and the traditions of his people.

The account begins with him unequivocally placing himself at the scene, using first-person pronouns: “he saw a white man … a dead one in a large ship about eight miles off Grant Point … On the mainland near Smith Pt. + Grant Pt. he saw the tracks of white men and judged they were hunting for deer. The first time he saw the tracks of four white men and afterwards the tracks of three. He saw the ship in the spring before the spring snow falls and the tracks in the fresh spring snow when the young reindeer come of the same year. He thinks that the white men lived in this ship until fall and then moved onto the mainland. … When he went on board the ship he saw a pile of dirt on one side of the cabin door showing that some white man had recently swept the cabin. He found on board the ship four red tin cans filled with meat and many that had been opened.”

Puhtoorak’s story then shifts between the first and third person, depending on the detail. “They did not understand how to get into the ship so they cut through one side and when the ice melted in the summer she sank as the water poured in. After the ship sank they found a small boat on the main-land in Wilmot Bay. … The natives went all over and through the ship and found also many empty casks. They found iron chains and anchors on deck, and spoons, knives, forks, tin plates, china plates etc below. When the ship sank her masts stuck out of water and many things floated on shore which the natives picked up. He also saw books on board the ship but the natives did not take them. He afterwards saw some that had washed ashore. He never saw any stone monument or cairn on the mainland near where the ship sank. There was one small boat hanging from the davits which the natives cut down. Some of the ship’s sails were set.” (emphasis added)

Here Puhtoorak is careful to distinguish between what he personally saw and did – going on board, seeing a dead man, finding cans, seeing tracks, seeing books – from what “they” or “the natives” found – the small boat, and other items on the wreck, the masts sticking out of the water. He makes no direct statement as to having witnessed the later sinking of the ship, only speculating on the cause, a speculation that we now know to be in error. Does Puhtoorak’s use of “the natives” rather than “I” or “we” offer a clue that those statements indicate tradition rather than personal experience? A reliance on parsing pronouns is perhaps not the best strategy, but these considerations led me back to Marc-Andre Bernier’s idea – that Puhtoorak actually did find the abandoned vessel near Grant Point, but that it subsequently drifted, or was taken, to the south where it eventually sank. A more careful reading of other Inuit accounts seemed to offer previously-unremarked clues.

Gilder noted that the “first party” found the ship, and that this included Puhtoorak was confirmed by Schwatka, who noted that the discovery of the white men’s tracks “near Smith Point and Grant Point” was done by this initial small group of hunters “which he [Putoorak] accompanied.” If the above hypothesis is correct, we should find accounts from other visitors to the wreck that do not accord with Puhtoorak’s.

A decade before Schwatka’s interview of Puhtoorak, C.F. Hall was told many of the details by others who, by their own account, had not visited the site. Koo-nik, had part of a glass jar in her possession which “came from a large cask filled with glass jars near where the great ship was seen & was finally sunk at Ook-joo-lik.” She located the wreck in its southern position near O’Reilly Island, and recounted the discovery, even naming the first hunter to see the ship, “Ook-joo-lik Innuits were out sealing when they saw a large ship – all very much afraid but Nuk-keeche-uk who went to the vessel while the others went to their Ig-loo. Nuk-kee-che-uk looked all around and saw nobody & finally Lik-lee-poonik-kee-look-oo-loo (stole a very little or few things) & then made for the Ig-loos. Then all the Innuits went to the ship & stole a good deal.” Yet according to Gilder, Puhtoorak and his party did not extensively loot the ship but travelled light and “only took knives, forks, spoons, and pans; the other things they had no use for.” Puhtoorak does not name his companions, and it is certainly possible that Nuk-kee-che-uk was in his party, but we could also be hearing of a second discovery of the same ship in its southern position, giving us another alternative for Klutschak’s understanding of the sequence fall (discovery) – spring (pillaging) – after breakup (wreck).

Hall’s informant Ek-kee-pee-ree-a, an Utjulingmiut native, and therefore a reliable source for the wreck, prefaced his remarks by telling Hall that he had “heard” the natives tell of this ship. His account echoed Koo-wik, that “the party … began ransacking the ship … From time to time the Neitchilles went to get out of her whatever they could; they made their plunder into piles on board, intending to sledge it to their igloos some time after; but on going again they found her sunk, except the top of the masts … The ship was afterward much broken up by the ice, and then masts, timbers, boxes, casks, &c., drifted on shore.” (emphasis added)

McClintock certainly expected to be able to visit the wreck in 1859. The natives of Boothia told him of the wreck that was “forced on shore by the ice, where they suppose she still remains,” while others told him that “but little now remained of the wreck which was accessible.” They indicated that an old woman and a boy had been the last visitors to the wreck “during the winter of 1857-8.”

This extended ransacking of the ship is again quite at odds with Puhtoorak’s implied quick visit. Having seen the ship secure in her protective floe of one-year ice for over a year, the natives presumably looked forward to many seasons of productive harvesting of materials. They must have been severely disappointed on their return to see the masts protruding from the water. Puhtoorak noted that “many things floated on shore which the natives picked up,” but makes no mention of joining in this activity.

It is interesting that, as opposed to the second ship (HMS Terror) found far to the north, in no Inuit account exists of the actual sinking of this ship. The tradition was that the discoverers had removed a plank at the waterline to gain access, and that the ship flooded upon its supporting ice melting. This rationale is offered by Puhtoorak as well, but it cannot have been from his eyewitness experience, or anyone’s. It is not borne out by the condition of HMS Erebus as found in 2014, for there is no hull damage. Much more likely is that the abandoned ship, like all nineteenth-century wooden vessels, required pumping to keep afloat, even more so if her timbers had been strained by years of battling the ice. When the crew left she slowly filled with water, eventually to the point that when released from her supporting floe she sank. The condition of Erebus indicates that she did so relatively upright and gently.

As noted above the actual location of the wreck is roughly halfway between the two points (Grant and O’Reilly) specified in the Inuit recollections. With so much evidence pointing to the former, how did the latter enter the story? The final point concerns the tracks in the snow seen near the ship. Puhtoorak noted that he “saw the tracks of four white men and afterwards the tracks of three” and he was again quite specific that the tracks were seen “[o]n the mainland, near Smith Point and Grant Point.” As noted previously, this tradition persists to the present day, with the nearby island Aviumavik pointed out as the site.

The tracks of four men that then became three is often read as those of the final crew who abandoned the ship at Grant Point, one of the weaker men eventually haven fallen behind. But the testimony doesn’t support this. Schwatka recalled that Puhtoorak “saw the tracks of white men and judged they were hunting for deer.” Hall’s informant In-nook-poo-zhe-jook offered even more detail of these tracks, and confirmed that this was a hunting party for “one man, from his running steps, was a very great runner – very long steps. The natives tracked the men a long distance, and found where they had killed and eaten a young deer.” It is conceivable that what Puhtoorak saw were the tracks made by two distinct hunting parties.

Hall was told a slight variant of this by Koo-nik: “Do you know anything about tracks of strangers seen at Ook-joo-lik? The Innuits at Ook-soo-see-too saw when walking along the tracks of 3 men Kob-loo-nas & those of a dog with them … [Koo-nik] say she has never seen the exact place not having ever been further w or w & south than Point C. Grant wh is the Pt. NE of O’Reily [sic] Island. She indicates on Rae’s chart the places, recognizing them readily. Ook-soo-see-too the land E of O’Reilly Isle as she shows on chart. The vessel seen 1st & then little while after the tracks of the 3 Koblu-nans & dog seen on the land.”

The curious discrepancy between Puhtoorak’s “four men,” afterwards three men, and Koo-nik’s three men and a dog has again been glossed over. Yet these different sets of tracks, the four men hunting deer, another party of three, and three men and a dog, all confidently located by their finders, were in different places. Koo-nik noted on Rae’s chart that her tracks were not seen in the northeast, near Smith and Grant Points, but southeast of the eventual wreck site. Although her identification of the place is vague – east of O’Reilly – it has survived to this day as the name of a small modern islet.

Hall was certain that when the Inuit mentioned “Ugjulik” they were actually talking about O’Reilly Island, but he later extended Ugjulik as far as Cape Felix.

Hi Randall, Hall did mention O’Reilly explicitly, but he also gave the lat and long of the wreck, from the placement of an Inuit finger on his chart, as between Grant Point and Kirkwall. He also confirmed “Umiartalik,” that I first thought was referring to the wreck but now belief was more associated with the boat that drifted off the ship, as lying in the north. I don’t read his work as referring Utjulik to only the southern part of the area that was indicated.

My own theory is that Erebus was filling gradually, with the draft as usual a bit down by the stern. The Inuit came across the high bulwarks and ice chocks, and worked around to the natural openings at the lower level-the sternlights/windows. More likely these were boarded over by heavy wooden deadlights. They broke or dismantled this area to gain access. Then as the ship settled more, water rushes over the window comings and she fills and sinks…making the accounts line up, including the absence of any visible damage, given the current devastated state of the wreck’s stern.

Alex, that is a very elegant solution to the “missing planks” problem. Perhaps once the stern damage is carefully analysed we might find evidence to support it. It is certainly simpler than my own thoughts about holes in boats, and the always vexing boat/ship question.